“The sign says Hall of Mirrors, but when you enter you find it is more than a simple hall. You are met not with floor-length unadorned planes of mirrored glass, as you half expected, but hundreds of mirrors of varying sizes and shapes, each in a different frame.

As you move past one mirror reflecting your boots, the mirror next to it shows only empty spaces and the mirrors on the other side. Your scarf is not present in one mirror and then it returns in the next….

As you walk farther into the room it becomes a field of endless streetlamps, the stripes repeating in fractal patterns, over and over and over.” –The Night Circus

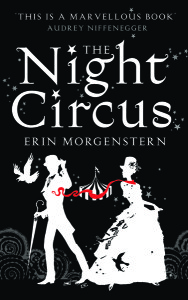

The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern is a beautifully crafted story over 500 pages long, yet it certainly doesn’t feel that way. The novel is about two lovers bound to each other since childhood. Unbeknownst to them their destinies are intertwined in a competition where only one can be left standing.

Celia is a young girl when her mother commits suicide and she is brought to her father, the great illusionist Prospero the Enchanter, otherwise known as Hector Bowen. To win a bet with the man only known throughout the book as Alexander or Mr. A.H, Bowen commits his 6-year-old daughter to participate in a game. Alexander adopts his player, Marco, just three years Celia’s senior, from an orphanage and begins to teach him all he knows about illusions.

When the Night Circus first came to fruition from the great and eccentric mind of Chandresh Christoph Lefevre, Celia and Marco had no idea that they were to be pitted against each other. But once the event was underway for several years they both realized that they had been set in opposition to each other from the start. They fall in love anyway and their relationship sets off a domino effect of events resulting most often in the deaths of beloved circus employees.

While Marco, with his magical intelligence, holds the circus together with charms (such as slowing down everyone’s aging so that the circus employees seems to never mature), Celia goes on a mission to end the competition and keep everyone she loves out of harm’s way.

The plot is the strongest part of the book and it will keep the reader flipping the pages. Morgenstern undoubtedly knew exactly how the circus should unfold in her mind, and how the characters’ interactions and discoveries of each other would develop. Another striking aspect of the book is Morgenstern’s brilliant descriptions: each beautiful old home, every musty library, and every inch of the circus is filled with beautiful images, and she makes it easy for one to sink into the setting: “The entire compartment looks like an explosion in a library, piles of books and paper amongst the velvet-covered benches and polished-wood tables. The light dances around the room with the motion of the train, bouncing off the crystal chandeliers.”

The characters are all quirky in their own ways, but while reading the story, I felt like I never got to really know Marco and Celia as well as I would have liked. They’re in love, but you never really see it develop except for the fact that they were smitten the moment they saw each other. But they hardly have interactions in which I felt their love over their lust. The rest of the cast and their reasons for being in The Night Circus, however, are so worth the read.

Before you pick up the other well-known circus-related book Water for Elephants, pick up The Night Circus. The Night Circus is much more fun and has a more developed story and setting, and believe me, by the end of it you’ll be hoping for a movie, and a real Night Circus you can attend.

“I just think some women aren’t made to be mothers. And some women aren’t made to be daughters.”

“I just think some women aren’t made to be mothers. And some women aren’t made to be daughters.”